I’m not a doctor. This article is based on my own experience. Before making any major changes to your diet or exercise routine—especially if you’re planning an aggressive weight loss and/or fitness program—please consult with your medical doctor.

Most people who start dieting look to their TDEE (Total Daily Energy Expenditure) to decide how many calories they should eat. On the surface, it makes sense: TDEE is the total number of calories you burn each day through a mix of your BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate) plus all your activity (walking, workouts, even fidgeting).

But here’s the catch: TDEE changes a lot from day to day.

Take a reasonably active adult as an example. On a day when they exercise, walk more, and stay on their feet, they might burn around 2,400 calories. But on a quieter, sedentary day, they may only burn 1,800–1,900 calories. That’s a swing of 500–600 calories in a single day.

Now imagine eating the exact same number of calories every day while aiming for a deficit. On your “high burn” days, you’re in a healthy 300–400 calorie deficit. But on your slower days, you might slip into a 300–400 calorie surplus without realizing it. Over time, this back-and-forth can make fat loss frustratingly slow—or stall it completely.

That’s why I personally don’t use TDEE as my guiding number. Instead, I set my nutrition by my BMR.

What BMR Is (and How It’s Calculated)

Simply put, your BMR is the number of calories your body burns at rest—just to stay alive. It covers essentials like breathing, circulation, cell repair, and organ function. Think of it as your body’s “baseline fuel requirement.”

If you really want to know how the math is math’d, here you go: the most common formulas to calculate BMR are:

1. Mifflin-St Jeor Equation (simple, widely used):

For men:

BMR=(10×weight in kg)+(6.25×height in cm)−(5×age in years)+5

For women:

BMR=(10×weight in kg)+(6.25×height in cm)−(5×age in years)−161

2. Katch-McArdle Equation (more accurate, the method I like to use):

BMR=370+(21.6×lean body mass in kg)

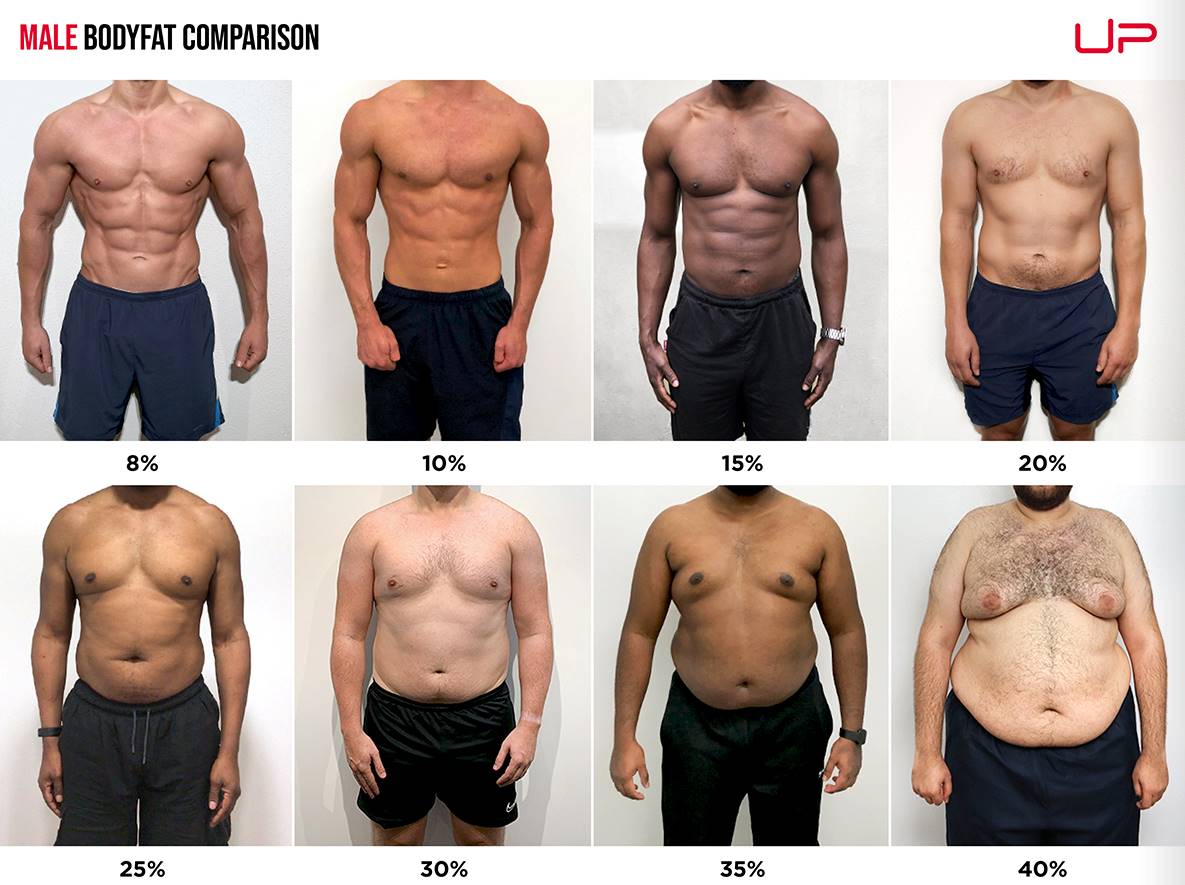

To use the Katch-McArdle formula, you’ll need a reliable way to measure body composition. A good smart scale can give you fat % and lean mass. Check out my Health Stack article, where I cover the scale I use. Although I prefer the most precise methods possible, if you don’t want to buy a scale just yet, you can simply Google a “male/female body fat % photo chart” to get a decent estimate. Here’s one that I found, to give you an example:

Pro-tip: Once you have your body fat percentage, use this prompt in ChatGPT or your favorite AI tool:

“I’m a X year old, X ft. X in. tall male/female, weighing X lbs., and X% body fat. Please calculate my BMI using the Katch-McArdle formula.”

And voila! You’ll have your BMI!

What TDEE Is (and Why It Fluctuates)

Once you know your BMR, you can estimate your TDEE by multiplying it by an Activity Factor:

Sedentary (little or no exercise): BMR × 1.2

Lightly active (light exercise 1–3 days/week): BMR × 1.375

Moderately active (moderate exercise 3–5 days/week): BMR × 1.55

Very active (hard exercise 6–7 days/week): BMR × 1.725

Extra active (physical job + training): BMR × 1.9

This gives you an estimate of your daily burn. But again, your actual daily burn can swing up or down hundreds of calories based on real-world activity.

An Example: Turning BMR Into a Calorie Budget

Let’s say a 40-year-old man, 5’10” (178 cm), weighing 170 lbs (77 kg), at about 20% body fat runs the numbers:

Mifflin-St Jeor BMR: ~1,660 calories/day

Katch-McArdle BMR: ~1,630 calories/day (using lean mass)

That’s pretty stable! For simplicity, he could set his intake target at ~1,650 calories per day. Then, whatever activity he does—whether it’s a 400-calorie workout, a 200-calorie walk, or a busier day on his feet—becomes a bonus calorie burn, driving his deficit deeper without changing his food plan. The best way to check your active calories burned throughout the day is to use a fitness tracker like a Garmin, Apple Watch, Fitbit, WHOOP, Oura, or the dozens of other devices on the market. Check out my “Health Stack” acticle for some information on the trackers I use and why.

How Fat Loss Actually Works

Here’s where the math comes in:

Roughly 3,500 calories burned = 1 pound of fat lost.

To lose 1 pound per week, you’d need about a 500 calorie deficit per day (since 500 × 7 = 3,500).

In the example above, if our 40-year-old man eats at his BMR of ~1,650 calories and burns an average of 2,150 calories per day, he’s running that ~500-calorie deficit. Over a week, that adds up to about a pound of fat.

A Word of Caution: Protecting Lean Mass

While a 500-calorie daily deficit is considered safe and sustainable for most people, going too aggressive can backfire. Very large deficits (say, 800–1,000 calories per day) raise the risk of losing lean body mass (muscle) along with fat. That’s not only unhelpful for body composition, but it also slows your metabolism.

To protect muscle while dieting:

Strength train regularly. Resistance training tells your body to hold on to muscle.

Get enough protein. Aim for 0.8–1.0 grams of protein per pound of body weight daily if you’re in a deficit.

Avoid extreme deficits. A steady, moderate deficit paired with exercise will preserve lean mass better than crash dieting.

The Budget Analogy

Think of it like money management.

If your income (TDEE) swings between $1,800 and $2,400 each day, it’s hard to set a spending plan. But if you budget based on your guaranteed minimum income (BMR), you’ll always be safe. Any “extra income” (calories burned from activity) is like surprise savings.

Why This Works for Me

By sticking to my BMR intake, I’ve eliminated the stress of adjusting calories daily. My deficit is predictable, my routine is simple, and my mindset is steady. And when I do get extra activity in, I know I’m only accelerating my progress.

If you’ve ever struggled with inconsistent results on a TDEE-based approach, shifting your perspective to a BMR-based budget might be the key to making weight loss more consistent—and less frustrating.

Again, just to make it crystal clear: I’m not a doctor. This article is based on personal experience and general research. Everyone’s body is different, and before making significant changes to your diet or exercise—especially aggressive calorie restriction or intense training—you should consult with your medical doctor.